Location: Wettgasse 10 – Bad Mergentheim

The Würzburger family is the family that paid the highest blood toll among the Jews of Mergentheim. All seven family members were murdered in camps.

Hermann Fechenbach wrote about the family:

“The poor Würzburgers, who had left their native Hagenau in Alsace in 1918 out of German patriotism, were now tortured to death in a concentration camp as thanks for their loyalty.”[1]

The Würzburger family consisted of seven people: the siblings Samuel (1870-1943), Rosa (1872-1942), Lina (1877-1942) and Ferdinand (1874-1944) and his family.

In view of Fechenbach’s statement, it can be assumed that the siblings had moved from Hagenau. However, the place of birth of the Alsatian siblings is irritating – all four siblings were born in Siegelsbach near Sinsheim. It would be conceivable that the family moved to Alsace, which had been German since the Franco-Prussian War, only after Lina’s birth in 1877.

Of the four siblings, only Ferdinand founded a family. On August 15, 1920, he married Ida Sommer (1889-1944) from Königheim. The couple had two children, Selma (1921-1942) and Bruno (1930-1944).

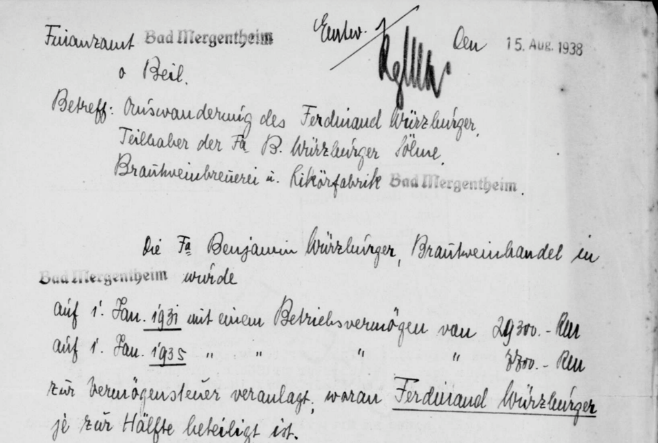

The family made a living, as evidenced by preserved tax records from the time of the Weimar Republic. Samuel and Ferdinand operated the “Liquor and Spirits Factory B. Würzburger Söhne” in Bad Mergentheim, whereby the company name indicates that the father Benjamin had already founded the company. The business relations of the liqueur factory were not limited to the region, but existed throughout the empire, reaching into numerous cities, such as Breslau, Berlin, Hamburg.

Nevertheless, the family was certainly not rich. Most of the time, the company employed only one or two workers, and even the residential house was rather cramped for 7 people. In total, two apartments had 66 and 40 square meters, respectively.

It is obvious that after 1933 the economic repression by the Nazis increased and the pressure on entrepreneurs and companies grew, and so it is not surprising that Samuel Würzburger fled to the Netherlands in 1937. In connection with Samuel’s flight, an exchange of correspondence between Ferdinand Würzburger and the tax office from 1938 appears particularly perfidious. On September 10, Ferdinand Würzburger reported under “outstanding debts” a liability of his brother “S. Würzburger, Rotterdam” for 2595,- to the Würzburger company. The tax authorities reacted to this on October 6 with the notice that this claim was to be assigned to a domestic foreign exchange bank and that Ferdinand was to “provide the exact address [of his creditor Würzburger, who had fled from the Nazis!

It is certain that Ferdinand Würzburger was also considering emigration. This is suggested by the tax documents of August 15, 1938, which state as subject: “Emigration of Ferdinand Würzburger” [see photo]. In a statement of assets for the tax office dated September 10, 1938, however, Ferdinand Würzburger formulates “There is still no prospect of emigration for me. As soon as this should be the case, I will give notice of it.” It is known that Ferdinand Würzburger submitted an offer to sell the residential and business premises to four businessmen he knew personally. It is known from one interested party that the deal did not materialize because the business appeared outdated. If one considers that the emigration possibly failed because of this….

Finally, a file cover refers to the end of the company. Lapidary it says there: “On 31.12.1938 trade stopped!”

This date was not self-chosen. Rather, the “Ordinance on the Use of Jewish Property” of December 3, 1938, required Jews to sell or liquidate their businesses “within a certain period of time.

State Archives of Baden-Württemberg, State Archives Ludwigsburg K28/Bü45, Permalink

In 1938, the Würzburger family lost its livelihood along with the company. But worse was to come.

“On November 8, 1938, the Nazi hell let loose all the devils, so that the temple desecrator Belshazzar, King of Babylon, stood like an orphan to Hitler. In this so-called unforgettable Kristallnacht all synagogues in Germany were torn down, defiled and burned, Jews were murdered, beaten and dragged to concentration camps. […] The interior of the [Mergentheim] synagogue was smashed and the Holy Ark smeared with pork, prayer books, notebooks and inkwells in the school and the window panes, everything was fanatically torn and smashed. No Jewish house was spared, and the inhabitants were defenseless against the most brutal abuse. The last synagogue director, Ferdinand Würzburger, was still able to save the objects of worship in the synagogue; he handed them over to the shipping agent Mühleck for safekeeping.”[2]

writes Hermann Fechenbach about the events of the Reich Pogrom Night in Bad Mergentheim.

Ferdinand Würzburger was the synagogue leader during this dark time, which reflects the prestige he enjoyed within the Jewish community – although he did not move there until after 1918.

The desecration of the synagogue weighed heavily; it now deprived the Jews of their spiritual and social center in addition to the loss of their civil rights and economic livelihood.

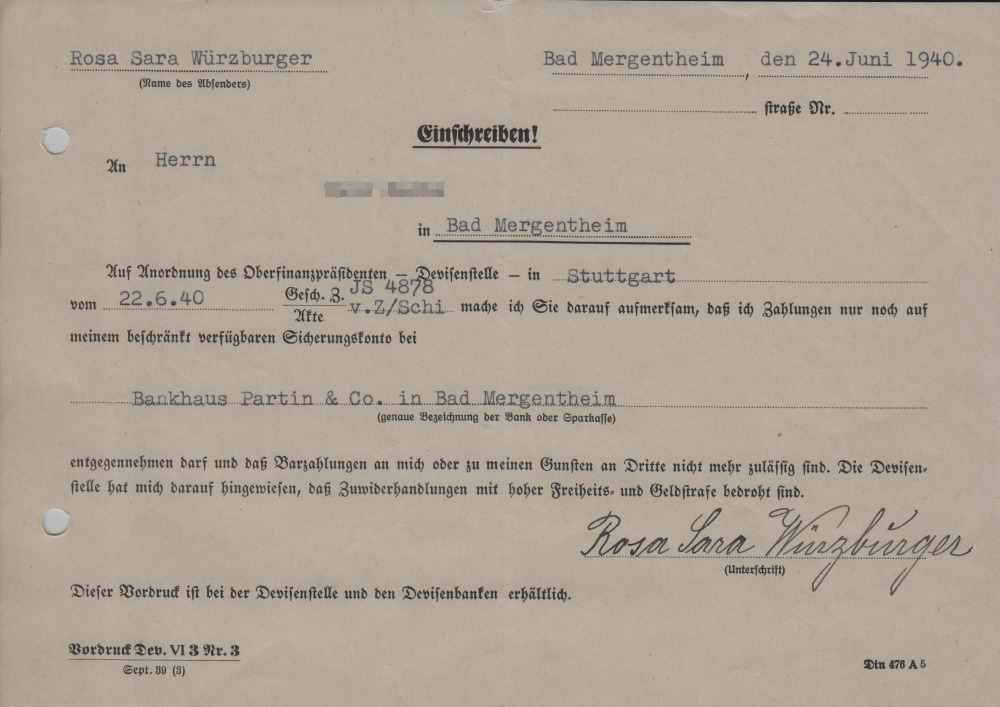

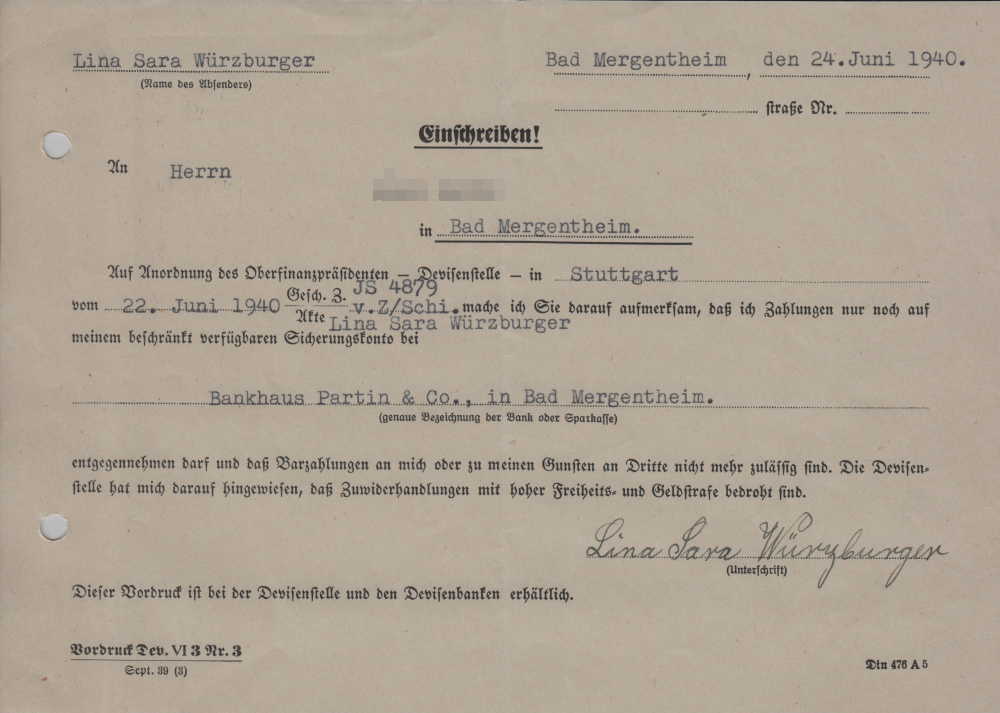

After the family had already had to give up their business in 1938, they finally lost their home in 1940. In the second half of the 1930s, as mentioned above, Ferdinand Würzburger had still been looking in vain for a buyer for the property, but on July 8, 1940, it was sold to a colonial goods wholesaler in Mergentheim. From August on, the still existing account records of all four siblings show rent payments to “Haus Berg” in the amount of RM 7.50 per person – presumably Haus Berg was a so-called “Jewish house” (it is conceivable that it was the property of Julius Berg, who had emigrated to Palestine in 1937, at Ochsengasse 18). The personal property of the Würzburger family was already very manageable at this time. Presumably, with the move out of Wettgasse, the remaining household goods also had to be given up. On October 9, 1940, there is at least a receipt of payment of 110,- RM each on the accounts of Rosa and Lina. The entry reads: “Deposit auctioneer Müller here”.

The accounts of the siblings all bear the red blocking note “Limited available security account”, which meant that the unmarried sisters could only dispose of 180,- (from 1942 reduced to 120,-) RM per month and the family of Ferdinand Würzburger, which after the deportation of the daughter only had three members, had 400,- (from 1942 180,-) RM at their disposal.

The only traces of life that can be personally attributed to Lina and Rosa Würzburger are their signatures on the forms with which they informed the buyer of their house that the sale price had to be paid into a restricted security account.

The next and last trace of life of all members of the Würzburger family who remained in Mergentheim is their name on the deportation lists.

Selma Würzburger (July 10, 1921- May 6, 1942), the daughter of Ferdinand and Ida, was the first to be deported.

In 1940, the 18-year-old was arrested for so-called “racial defilement” – it is interesting to note in this context that, according to a narrow interpretation of the Nuremberg Race Laws, “racial defilement” could already be present if kisses and endearments were exchanged that were due to sexual urges. Imagine an 18-year-old girl experiencing her first love….

Selma Würzburger was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp on May 10, 1940, where she presumably had to perform slave labor in the SS textile company Texled.

“In the industrial yard, prisoners had to work up to twelve-hour shifts in the tailor shop, at first making concentration camp prisoner clothing, and later mainly making equipment and commodities of a military and civilian nature, primarily from textiles and leather. […] These women […] were […] not readily replaceable, yet they too received inadequate food rations and were subjected to mistreatment and harassment, especially when they failed to meet the nearly impossible production target.”[3]

By April 1942, Selma could no longer cope with the workload. According to Nazi guidelines, medical commissions drew up lists of prisoners who could no longer be “put to useful use,” so-called “ballast existences,” who were gassed. Since Ravensbrück did not have its own gas chambers, Selma Würzburger and more than 1,600 other women prisoners, about half of them Jewish, were transferred to the Nazi killing facility at Bernburg, where she was murdered on May 6, 1942.

On April 24, 1942, the next family member, Lina Würzburger (May 8, 1877 – April 26, 1942), was deported. The destination of the journey was the transit ghetto Izbica.

Hermann Fechenbach writes about this transport, which Lina had to endure together with Rosa Ledermann (b. 1877), Hanna Rothschild (b. 1892) and her daughter Käthe (b. 1926):

“They, too, were taken to the railroad station under police supervision like felons and transported to the Stuttgart-Weißenhof collection camp. Here there were 278 persons who were shipped to Izbica, Lublin district, in cattle cars on April 26, 1942, and none of them came back. Those who had not already perished from the hardest drudgery and from hunger in the first few months were handed over to the Belzec or Majdanek extermination camps as “unfit for work.”[1]

In Izbica, Lina Würzburger’s trail is lost, but it can be assumed that the 65-year-old could not withstand the ordeals for long. In general, it is questionable whether Izbica still had a real ghetto function in April 1942.

Robert Kuwałek in his work “The Izbica Transit Ghetto” puts forward two hypotheses. Either the purpose of the deportation to Izbica had served propaganda, which was to suggest to the family members who remained behind that their relatives were merely being relocated to work in the East – in the case of 65-year-old Lina Würzburger, this would have been unconvincing – or the gas chambers in the death camps had not yet had sufficient capacity. The fact that numerous transports took place in October and November 1942 substantiates this thesis.[4]

Am 20.8.1942 wurden die letzten Familienmitglieder, mit dem zugleich letzten aus Mergentheim abgehenden Transport, deportiert. Ziel der Fahrt war Theresienstadt.

On August 20, 1942, the last family members were deported with the last transport leaving Mergentheim. The destination of the journey was Theresienstadt.

Ferdinand Würzburger was deported there with his wife Ida (born 1889), his son Bruno (born 1930) and his sister Rosa (born 1872) along with eleven other Jews.

Rosa died in Theresienstadt already on September 8, 1942.

On April 6, 1944, Ferdinand died in Theresienstadt.

On October 9, 1944, a transport with 1,550 people arrived at Auschwitz coming from Theresienstadt. 191 women and several dozen men are admitted to the transit camp; the others, among them Ida and Bruno Würzburger, are murdered in the gas chambers on the same day.

Samuel Würzburger is the only member of the family to escape from Germany. On February 15, 1937, he emigrated to Holland. The only existing reference to his place of residence, Rotterdam, is found in the already mentioned correspondence of his brother Ferdinand with the tax office from 1938. Whether Samuel Würzburger had planned to wait in the Netherlands until the “brown spook” was over or had planned to continue his journey to the USA or Great Britain, we do not know.

After the Dutch surrender on May 14, 1940, the measures against the Jews living in Holland began. At that time, Samuel Würzburger lived in Amsterdam at Herengracht 121/1. Herengracht is the innermost of the three canals belonging to the Amsterdam canal belt, concentrically laid out around the old city of Amsterdam.

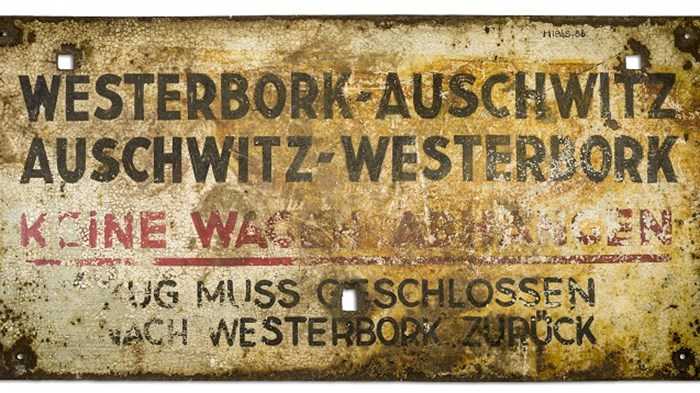

It is not known when Samuel Würzburger was deported to the “Polizeiliche Judendurchgangslager Westerbork”. Only the date of his further deportation to Auschwitz is known.

Image: Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork.

On 29.01.1943 a transport with 419 women and girls and 240 men and boys left Westerbork. According to Nazi doctrine, the deportees were Jewish and therefore undesirable elements. The transport arrives in Auschwitz on January 31, 1943. Only 50 men and 19 women initially remain alive as prisoners; the other 590 people, including Samuel Würzburger, are murdered immediately in the gas chambers. Samuel Würzburger dies on February 1, 1943.

1. Fechenbach, Hermann: Die letzten Mergentheimer Juden. Reprinted by the city of Bad Mergentheim on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Hermann Fechenbach. S. 179f.

2. Die letzten Mergentheimer Juden, S. 160f.

3. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/KZ_Ravensbr%C3%Bcck#Situation_der_H%C3%A4ftlinge

4. vgl. Robert Kuwałek: Das Transitghetto Izbica. In: bildungswerk-ks.de. Quoted from: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghetto_Izbica

Laying date: 07. Oktober 2021 Sponsorship: Ferdinand Würzburger - present | Samuel Würzburger - present | Lina und Rosa Würzburger - present | Ida und Selma Würzburger - Brigitte Kaupat | Bruno Würzburger - Axel Bähr Author: RH